I am sure that many of you have seen the Black Swan with Natalie Portman and have a lot to say about it. But I begin today with the other Black Swan and where it has led me. And maybe how it explains a lot to me and maybe it will to you as well.

The Black Swan was a book title. And one that I read. Nicholas Nassem Talib, author. He was talking about how some things just seem outside of our reality, our expectations. He spoke about how all swans were white. Until someone went to Australia and found that some were black. Hence the title. I found the book to be a very interesting read, helping to inform me and remind me that the folks on TV News, or in the political leadership, or in the Science journals, or the “Suits” in Hollywood, or many others to whom we look for guidance may not be ready for what is coming next. After something comes, like 9/11 or 3/11 or the Arab Spring, which we did not expect or if we did, had no realistic range in mind of its consequences, there are some who rush to explain that they saw it all along and now we should listen to them. Talib reminds us that nobody knew. And that we should not think that there will be another one. We might not know that an airliner attack would trigger two wars that would last a decade or more, that really big earthquakes can trigger really big problems with nuclear power, or that there could be a rapid end to dictators in many countries in the same year and who might come to rule next.

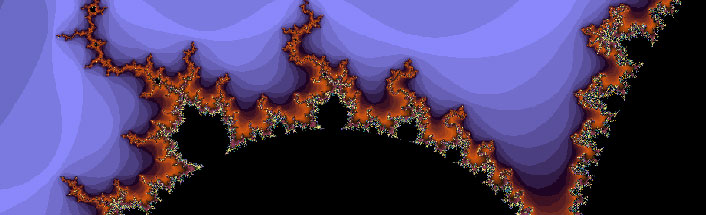

So, there I was reading along. And whose name should pop up? Someone I never knew and yet, without his ideas, my work would still be stuck in darkness and organic chemistry, the wet side. Talib introduced me to Benoit Mandelbrot, the multi-faceted math guy. And the father of Fractals. (Cute little guy with the double cowlick? No, you must be thinking of someone else.) No I mean Fractals. The idea that some things can be imagined that have repeating patterns of shape as one changes scale. Now, I am sure that is not the definition in his book. Or say that one can take something apart and the smaller parts resemble the larger ones. That is closer.

Now, who cares? Really? Sometimes things just creep into our lives unnoticed. Remember the first Epson Color Stylus printer? We had inkjet printers before that one. But that one changed the way we looked at desktop printers. It made pictures on “plain paper.” They looked something like photos on photo paper. Not quite, but close. And Epson got better at making printers. I have a long list of Epson printers that I bought, longer than my list of cars that I have owned, certainly a lot longer than the list of girls I may have dated in High School. They all had something in common. (The printers!) They depended on fractals to make the little files into bigger, photorealistic ones. We did not know it at the time, but those little squirty print heads were spitting out an image that was using only a portion of the pixels from out digital pictures, maybe around 100 or so per inch, and were using special math formulas based on the fractal idea to invent the rest. Wow. At least that is what I think. So how did it change my work?

I began my career in the darkroom. Smelly chemicals, safe-lights or total darkness, handling film, paper, more film, holders, paper safes, roll easels, enlargers, and really big enlargers. I began my movie backdrop career in the biggest darkroom in the world. Over 20 feet high, about 30 feet wide and more than 60 feet long. The enlarger was on a track, sort of reminded me of a very narrow railroad with a loud, bright xenon light blasting through a negative held between two sheets of glass and zooming out through a lens to land dimly on a distant “board” that was really an oversized garage door coated with cork and canvas. Some of my readers remember slide projectors. Not a lot of difference, but only a much bigger scale. Over time things got more modern, but we still were projecting light. But one day, it all changed.

So, to replace this, we got a box with a three lasers inside. Pretty big box, but still a lot smaller. Maybe 8 by 8 by 8 feet or so. And it seemed to be the same idea. Light shining through the darkness from small to big. But actually it did not change size at all. It was a laser light. Coherent. And size stable. So, how did we get it bigger? How did we make it huge? Fractals. Yeah, the same thing that Epson did. Really elegantly. So much so that it made the inkjet seem a bit coarse. The sneaky folks who wrote the software that controlled this box used fractals to fill in the blanks between the pixels. The box printed at 200 pixels per inch. But in doing so, because the pixels actually landed perfectly, it was equivalent to the 2000 pixels from an inkjet. Not bad for a box from Northern Italy. The red, green, and blue lasers painted the film with pure light so well that we could make big pictures of clarity and beauty from our small digital files. Not tiny files, but they were often enlarged 10 times or so to print. That means that for every original pixel, nine more had to be created to make it to the next one. Ouch. But Mandelbrot’s Fractals could fill in the missing detail. And that is the point. Missing detail filled in. Not just grainy structures on a negative making a bigger image like in the first darkroom I used.

So, is this better? Or worse? And does it make me more important or less important as the photographer/ artiste? Does it just make me the loader and unloader since someone else wrote the program to fill in the blanks?

I wrapped up some work on a new film a few months ago. I can’t tell you which one yet, but you might be able to figure out what was shot in NYC this year and has had plenty of press. And I have seen a report that it is using the new tiny form factor camera from the Red folks, in fact a couple of them per tripod. But we will leave the rumors for another post.

I found myself testing the full resolution images on this one. I really did not have to. I mean, I showed pictures to the art department that had every pixel from my original work and they approved them. But was that the end of my responsibility to them? I decided that it was not. Why? Because the algorithm used to apply the fractal math to make the pictures bigger was acting on those pictures and sometimes, just sometimes, the autopilot function of the software saw too much and invented what I did not want to have invented. It filled in the missing space with the wrong interpretation. So I tested small areas, then I altered the files by painting or blurring or some other tweaking so that the big looked more like the little.

Was I perfect? No. But did I do my best? Yes. It might be just the right thing to trust your photographer/ artiste/ film loader/ printer. Because the eye is better than the algorithm. More about Talib and Mandelbrot later- on Roughness.

did not tihnk that there are websites left on the net with some content.

Hey there! Do you use Twitter? I’d like to follow you if that would be ok. I’m undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new posts.

Top article.

I value you taking the time to write this publish. It is extremely useful to me certainly. Value it.

Very interesting topic , thanks for posting .