What do we see when we come into this world? And what do we learn to do with that sensory input? Let’s have a look…

Sometimes I see a picture on facebook in someone’s album and it is sideways. That’s okay. I can turn my head if I really need to see it. It is a little disconcerting, but, heh… I can live with it.

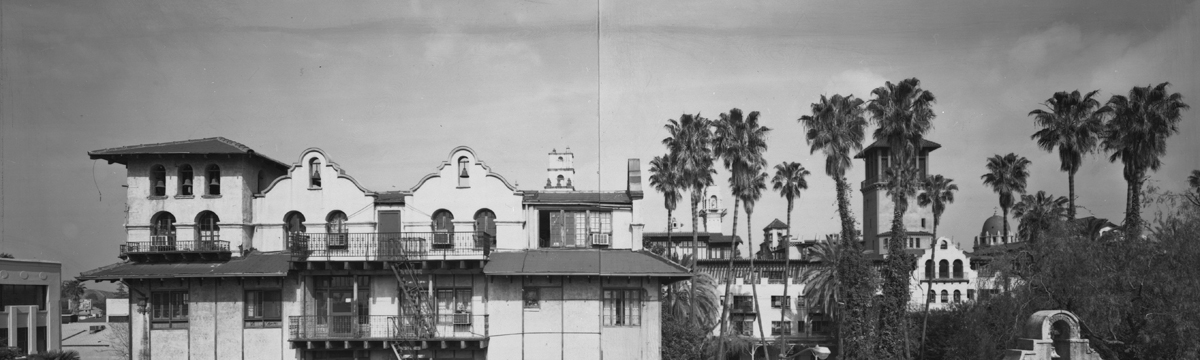

But what about my view camera? What do I see there? Those of you who have spent time with one know the secret truth. Everything is upside and backwards inside when you look at the image on the ground glass. Next time you see someone out with a camera on a tripod that has a cloth attached to the back, step up and ask to take a look. It will look something like the picture below.

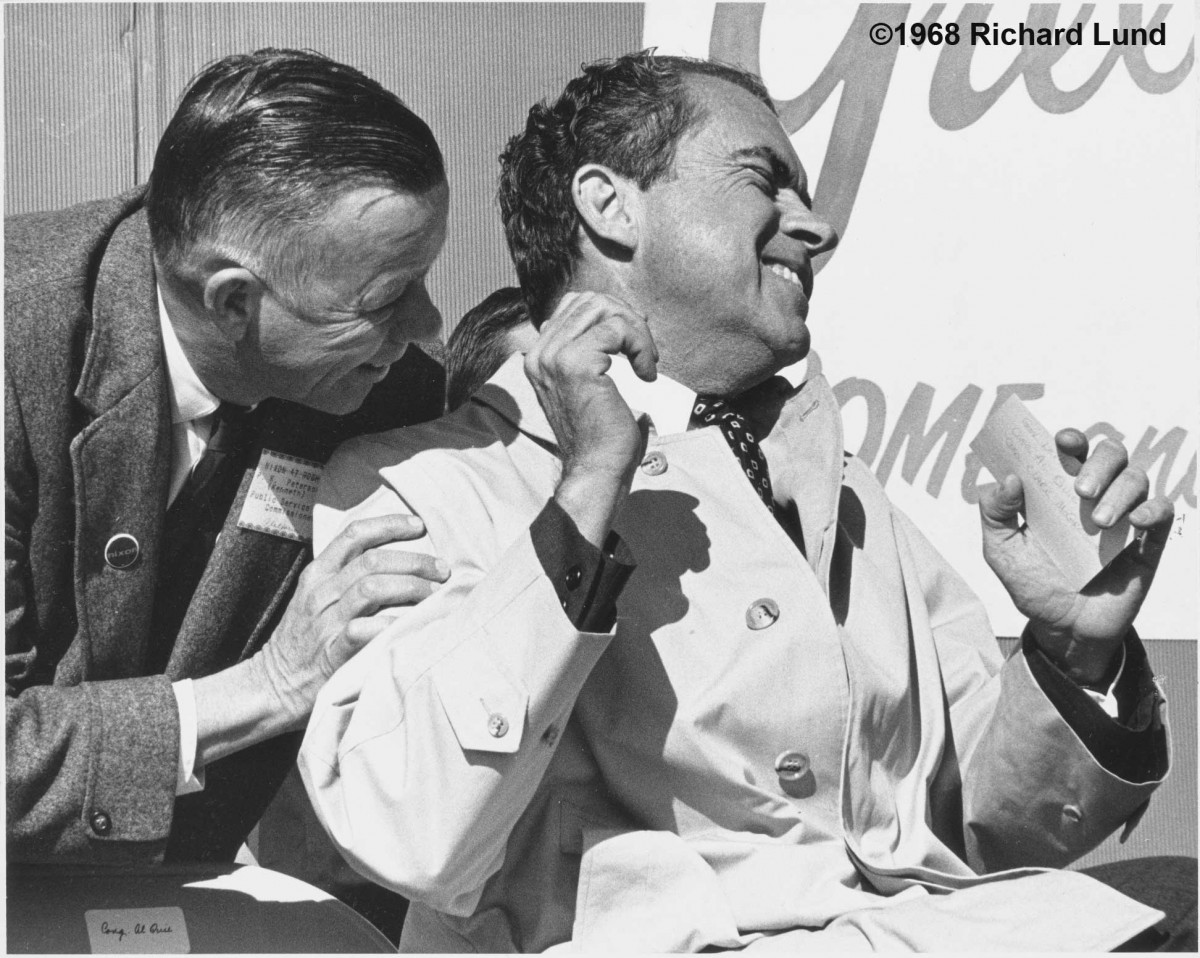

The grid lines are there so that one can adjust the image to be straight if one desires. Hey, I always liked to get things straight. Especially buildings. I remember Doc Baily on Fight Club talking to me after he got the scans from the buildings in Century City that I shot for him. He praised me because they were nearly perfectly straight. He only had to correct a little bit. I guess he was one of the first guys that I met working with wire frame and rendering. If you have another look at Fight Club, he did the exploding building sequences. For the work that IMDB counts as mine, this movie has the most sustained popularity. Doc Baily did his part right. I guess others did, too. 🙂

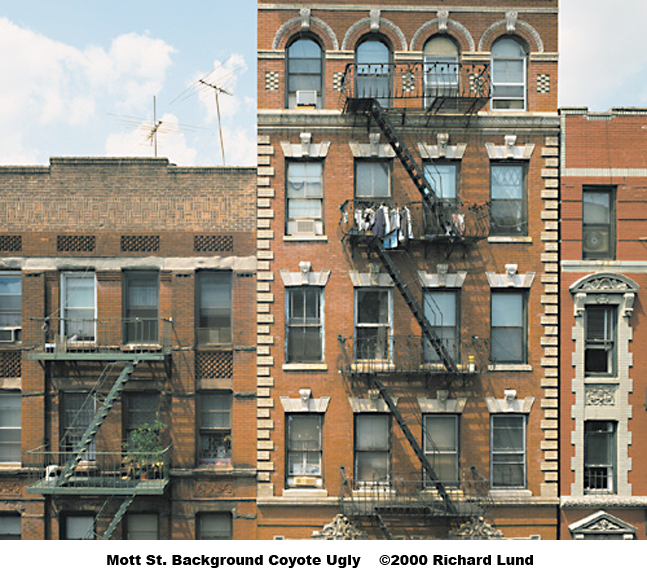

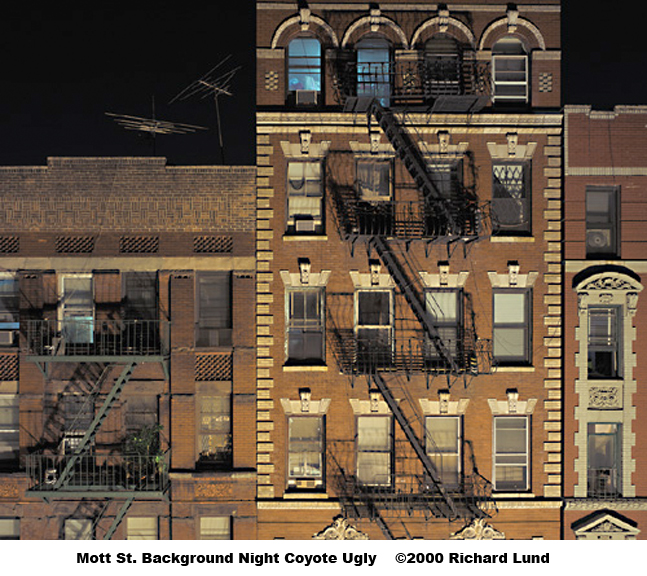

Before you get a headache, let me show you the building upside right. Okay?

So what about the baby thing?

I seem to have learned a lot from having children of my own. I still remember the day my first baby was born. My wife had gotten up early on a Sunday and was showering. Something happened. She fainted. I knew that she was in labor and I was getting ready to take her to the hospital. Oops. Now I had a soaking wet, naked, full-term pregnant woman passed out on the floor. Let me tell you, I was really glad that she woke up. We dashed to the hospital and in four hours and a little more out came my baby girl. The doctor had a bright light that he shined on the scene of delivery and my baby did not like that one bit. She was crying her little lungs out with her eyes completely shut. Not long after, they gave the baby to my wife and the light was no longer in her eyes. She stopped the crying and I still recall her opening her eyes and looking out at me. I can’t say for certain what she thought at the time, but I know that her eyes worked like all lenses do. The image they provided her brain was upside down and backwards. She was not all that interested in that stuff, of course. Newborns have a wonderful rooting ability and she wanted to nurse. She got what she wanted.

In the coming weeks, she started to notice more things. One day we were watching Little House on the Prairie, a popular television series at the time. Someone on the show began to sing the song Amazing Grace. My little one turned away from nursing to the sound. She seemed to recognize the song. We had sung the song to her before she was born. That was very interesting.

But back to baby vision. Have a look at this next picture.

She is using her hands to connect what she sees and feels. Visual processing has begun to correct what she sees.

We see this little girl using her hands and her eyes together. She is making sense from her environment. My first little girl had a nickname from me when she was a baby. I called her Private Finger. She would stick out her index finger and use it for her chief tactile investigative tool.

This illustrates my next point that our brains process or fix what we see. Years ago I read about an experiment on vision in the UK. Someone had rigged special glasses for people that turned things upside down and backwards. Volunteers were required to wear them all the time. In a few days, they began to see normally through the glasses. And if they took them off, the world was wrong visually. After the use of the glasses ended, all the people had their normal vision return in a few more days. (I find that the experiment has not been repeated easily, so some doubt, but think about it from the point of origin. We all learn to see “right reading.”) So it illustrates my point. Our brains figure out what we should see and show us the corrected view. Our brains do that first switcheroo and a whole lot more. Have a look at the next shot.

The lenses in our eyes are known as spherical lenses. That means that the image from the edge is curved. It might not seem like it, but that is because of your brain fixing things. You have learned about buildings and other things that stand upright. Perfectly straight. So your brain figures out what you need and presents what you know to be true. It takes a while to learn this stuff, of course, so don’t hire a two-year-old to build your next house, okay? But what else do we need to learn visually? Actually, quite a bit. One is color. Yes, color. Okay, so we start language skills by someone asking us about stuff and touching it. “Where is baby’s nose? Oh, there it is. And where is Mommy’s nose? Yes, that’s right.” And we read books or talk about color. Grass is green, the sun is yellow, skies are blue. Well, actually more cyan, but who tells a baby that?

I had trouble in kindergarten. Mrs. Zehren was my teacher. A very nice lady. So understanding and kind. Here’s one story about that. We had a classroom with tables and chairs in the front and a play area in the back with actual tools and stuff for the boys. Hammers, nails, saws, id est real tools. I guess the girls were stuck with blocks and dolls. One day, must have been around Thanksgiving, she passed out some papers. For those under a certain age, I will have to explain that some paper could be printed by a mimeograph mechanically to make lots of copies. And we got a very heavy, black line picture of a turkey, in side view, with the head on the left and with several highly stylized blocks of feathers, maybe six or seven of them arranged around the body of the bird. Our assignment was to color the picture and then we could be dismissed to go play. Simple. Right? Well, not exactly. I had my required eight Crayola® Brand color crayons. Black, red, green, blue, violet, yellow, orange, brown… I knew how to color. My hands worked fine. But my brain was stuck. I knew that turkeys were mostly brown and that their feathers had some variation in tone and some on color. And the big blocks must be divided into tiny little parts to make them look like a turkey. All of the other kids went to work. Feather one might have gotten red, then the next yellow or green, and so on. As long as they stayed inside the lines, they were doing a good job. And they all got to play. Except me. I could not figure out how to do it. I could not just color the feathers in one color each, yet I lacked the knowledge and confidence to make them look as I thought they should. I knew turkeys were different from what I saw on everyone else’s paper. The tension built until I could not take it anymore. I was frantic.

My solution was to…cry. Big crocodile tears. And the voice, quivering. “Mrs. Zehren, I can’t do it.” She must have been very wise because she let me go play. The tears were gone pretty quick. I wonder, looking back, if on that day my life’s course was set, to be a photographer. I often said that I did it because I couldn’t draw very well. Maybe it was also that I couldn’t color well enough as well. ¿Quién sabe?

So, babies learn to flip things, straighten things, and that certain things should have certain colors. We know that sunlight and incandescent lights have a different color temperature. Sunlight has a cooler look and old Thomas Edison style light bulbs have more red and are warmer in tone. In a few more years, the Edison bulbs will be gone from my state of California, replaced by flourescents and LEDs. But for now, most of my readers will admit that their friends look pretty much the same in their kitchen, out in the garden, at the beach, and maybe even in a dark night club. The reason is that we know what they should look like and fix the pictures that we see to match. We might see them wearing a red dress and even though the red dress would photograph on old style film differently in different light, one look and we know it is red. Or pink, or white. We don’t even have to think about it. Just gets done for us. Our brain, our vision.

And what does the baby see? I bet color. But what we have learned about how our eyes actually sense color has a real influence. Likely you have heard about rods and cones. In our eyeballs. The rods sense dim light and the cones see the bright stuff. It turns out that the cones don’t see much color, (well that is not exactly true. They see blue light and not red light, but we don’t see it as blue light, just as light.) But we still know what things are in that night club scene. The dress is red.

What we do see is what we expect to see. Hey, let me say it again. We see what we expect to see. Vi ser hva vi forventer å se. (That’s for my Norsk family. You do your own translation at Translate Google.) Cameras do not always record what we expect to see, of course. I guess that is one of my points. But what we expect to see is what we should present as we make photographs and cinema. Back to the cones.

There are three classes of cones. Tall, grande, and venti. Well, sort of. (Too much Starbucks coffee?) And these three sizes see different parts of the color spectrum. We measure color in nanometers (nm) of the wavelength, like a 650 nm wave is red, a 450 wave is blue. And we really have three basic peaks of color sensitivity, red, green, and blue. But we have two main color pairs in vision, blue-yellow (like a Swedish flag) and red-green (like Santa and Christmas). Let us agree to talk about those relationships in an upcoming post. We will talk about simultaneous contrast and more. And we had to talk about the brain and the eyes today to make sense of what is coming.

I learned some things from Kodak over the years. You know, the yellow box company. They have pretty smart engineers. One day they told me about the difference between sensitometry and densitometry. One measures the actual differences in color and the latter measures those differences as seen by people. In my early years of color printing, I could not afford the dial-a-color head on my enlarger. We used cut acetate filters instead. When we wanted to add yellow to the printing pack, we could take out the 20 Yellow and put in a 40 Yellow. In this case there would be no change in exposure time because the Yellow filters had the same filter factor of 1.1. But if i pulled out a 20 Red and put in a 40 Red, I had to recalculate from a factor of 1.5 to 1.9, if I remember correctly. Not because Kodak could not efficiently make a red filter, but because our eyes do not see red with the same intensity as we see yellow. And green is in between. Blue is another story, of course. But more about that at another time.

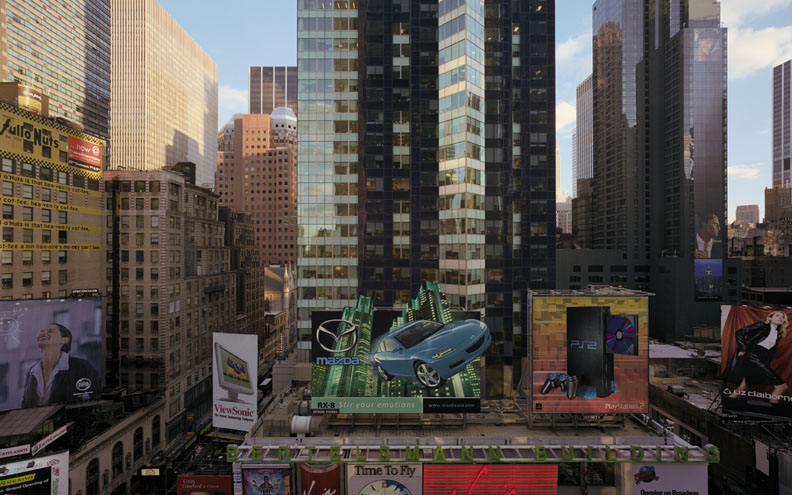

So I made a version of a picture with strong colored columns, not unlike the intended feathers in Mrs. Zehren’s mimeo paper turkey. But I pulled down the red and green and pumped the yellow and blue. For your comfort, it is “right reading.” Have a look.

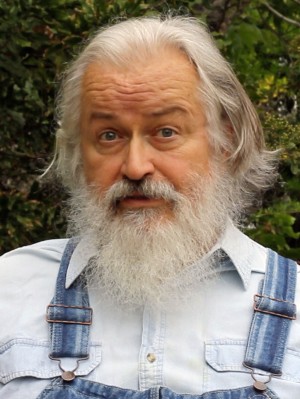

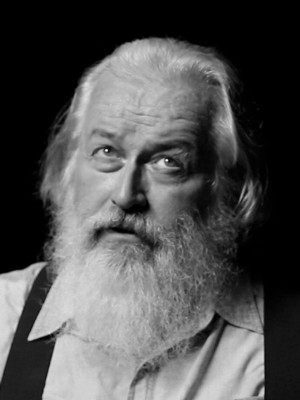

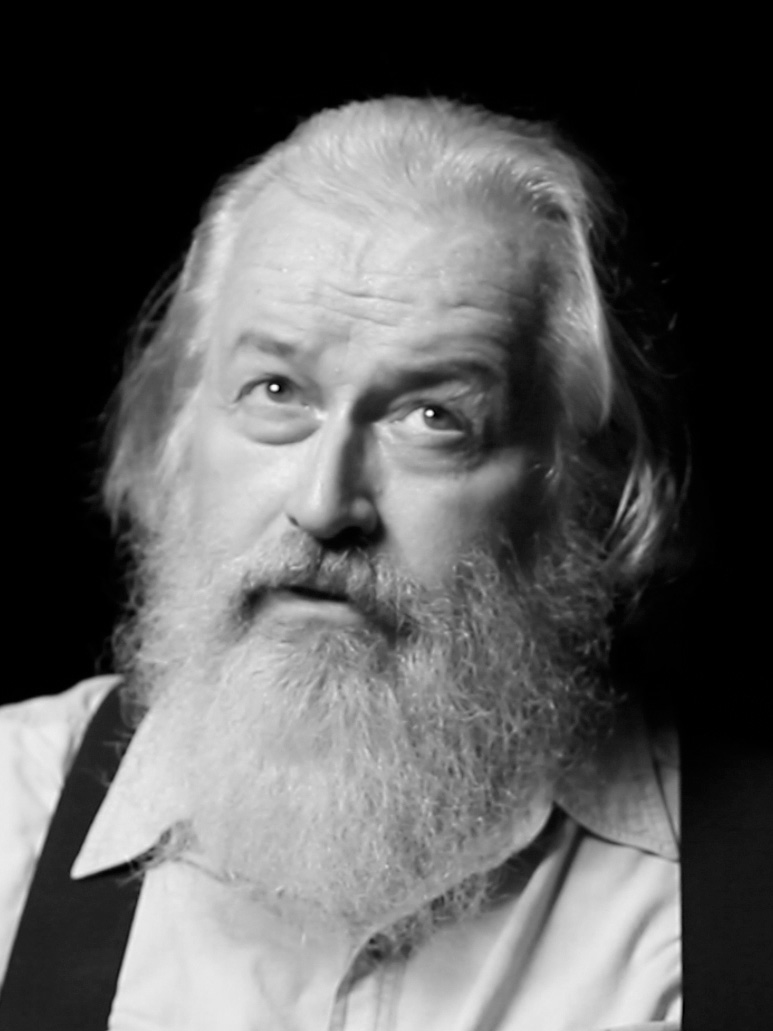

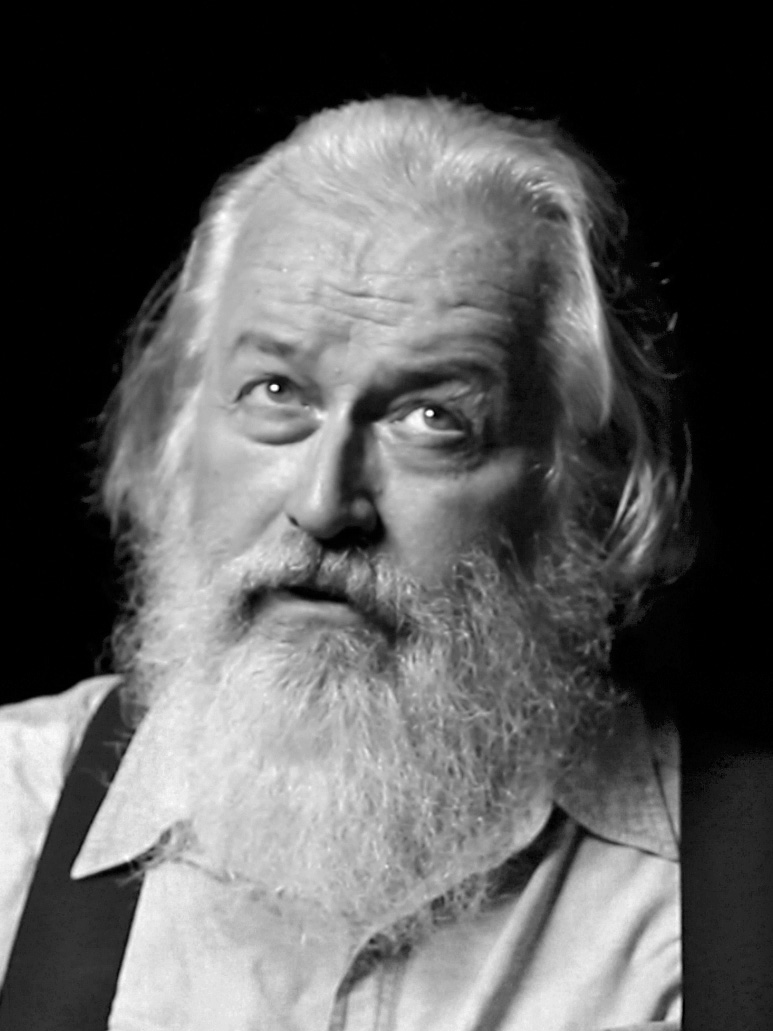

Here I am with some color adjustments to reflect the baby view. Blurred to simulate baby vision. Facial expression to simulate what? I have no idea.

In a coming post I plan to cover Delacroix and Newton. I will talk about the idea that we blend memories of what we have seen with current vision, and I will show some experimental color photos to see if we really see the color we think we see. Tune in. And share my site link if you like the stuff I make. Thanks.